Nori Seaweed, An Ocean Fortified Dietary Supplement

Nori is the Japanese name for a type of seaweed from the genus Porphyra that grows wild, like other sea vegetables, off of rocks along shallow coastal shorelines, mainly in the Pacific Ocean as well as the North Atlantic and Irish Sea.

Nori is considered one of the most domesticated of the Asian seaweed varieties. Extensively cultivated for centuries by the Japanese using traditional methods, most seaweed today is now ocean farmed on a much larger scale.

The marine algae is still a common everyday Japanese food incorporated into various dishes, but is most predominantly used to roll rice and other ingredients in the popular Japanese cuisine known as sushi.

The first use of nori dates back to 8th century Japan where it was harvested, dried and used as a type of paste. It wasn't until the end of the Edo Period (1603 to 1868) that the "nori sheet" was invented. This encompassed a special technique in which the seaweed paste is laid out on racks, similar to the Japanese paper-making process, to form thin rectangular sheets when dried.

Other species from the genus Porphyra also grow prolifically in the Atlantic Irish Sea. Known exclusively as laver in the British Isle region, it has been consumed as a standard sea vegetable in Wales for hundreds of years. Freshly harvested laver is typically washed and simmered into a dark green pulp, forming the traditional Welsh delicacy called laverbread.

Sea vegetables, like laver, became especially prevalent in the Western world with the macrobiotic health movement, popularized by Japanese teacher George Ohsawa in the 1960's.

It wasn't until the 1970's, along with the increase of sushi bars and Japanese restaurants, that American-style sushi using nori wrapping techniques became a popular trendy food. Soon after this time, nori sheets imported from Japan became widely available in health food stores and Asian markets across the U.S. for use in homemade-style sushi.

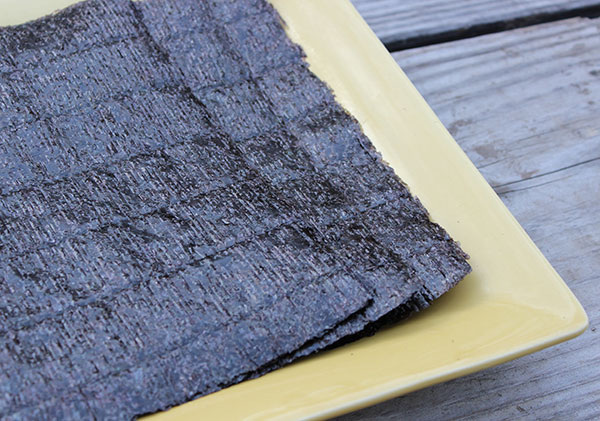

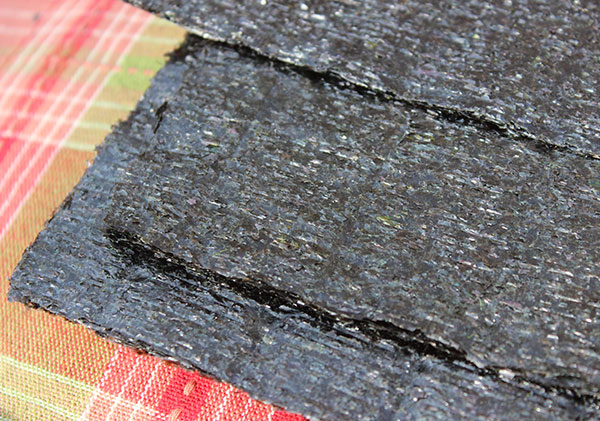

While laver has a naturally sweet and nutty flavor in its raw dried form, lightly toasting the seaweed tends to enhance these qualities. Therefore, it is traditionally toasted plain or toasted with seasonings like sesame oil and salt. This process turns the sheet a bright olive-green color. Raw untoasted varieties, usually a dark black-green to purple color, are also quite standard and thought to preserve greater nutritional value.

Although it is more common to find nori sold in sheets rather than as whole laver pieces or flakes, the crumbled seaweed can also be used in soups or atop meals as a salt substitute.

Laver, like other seaweeds, contains many phytonutrients, like minerals and polysaccharides that are not as abundant in land sourced vegetables. Seaweeds, because of their unique structure draw in high concentrations of nutrients through their leaf-like blades. Fertilized by the clean cold ocean waters in which they grow, dried sea plants, like laver or nori, offer a natural source of many vitamins and minerals often lacking in most cultivated plant-based foods.

Eaten periodically, laver can be a great whole food supplement helpful for amending possible dietary deficiencies. It contains significant amounts of vitamins and minerals, including a healthy balance of dietary iodine. It is also believed in some documented research to have some vitamin B-12 content.

In another study analyzing the antioxidants found in laver, evidence supports the notion that "laver contains bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols and flavonoids, which may have a positive effect on health."

What is Nori?

Nori, or laver, is classified as a red algae seaweed species that comes from the genus Porphyra (or Pyropia), which comprises close to 70 different species. The two main Asian varieties, growing in intertidal zones of the Pacific and Indian Ocean, include P. tenera and P. yeeziensis.

Porphyra umbilicalis, most commonly referred to as "purple laver", is primarily found in the North Atlantic and Irish sea where it is widely consumed as a popular sea vegetable. Other species of Porphyra also grow wild off the coast of North Western Pacific coastlines as well as the East Atlantic coasts of Maine and Canada.

Although Japanese nori cultivation is believed to be quite an ancient practice, updated seeding and growing techniques were discovered by the end of World War II, which revolutionized the Japanese nori aquaculture industry by the mid 1950's.

Asian Aquaculture Farming

Nori "farming", exclusively off the coasts of China, Korea and Japan, involves an advanced form of aquaculture in which the sea plants grow in controlled marine water settings suspended from floating nets at the sea surface.

The two main species cultivated are P. tenera and P. yezoensis. Different farms can produce different grades of nori depending on specialized growing and harvesting practices. This includes a deep understanding of the sea plant's natural growth cycles, especially spore germination and development. Seaweed quality is also affected by salinity and temperature of the seawater in which it is cultivated.

Fukushima and Seaweed Quality

It is a good idea to avoid aquaculture farmed seaweeds coming from the Tokyo Bay region south of Fukushima due to the 2011 nuclear disaster. Large scale farming production in Japan is primarily located in Southern regions around Ise Bay, Seto Inland Sea and around the Ariake Sea. We highly recommend buying your seaweeds from reputable sources, preferably organically certified selections (grow in controlled environments) or sources that test for radioactive isotopes and other toxic substances.

How are Nori Sheets Made?

Transforming fresh seaweed into sheets of paper-like nori is a definite art form and Asian cultures are the masters of this processing technique. Invented over 200 years ago, it arose as an adaptation of the Japanese paper-making process. Traditional sheet-making methods are a perfected skill requiring high quality fresh laver which is chopped, made into a slurry and then placed onto a framed screen. The frame is then lifted off the wet nori sheet, which is tilted and allowed to sun-dry on a bamboo mat.

Today, modern mechanized techniques are of course now commonly employed to increase sheet production.

Taste, color and texture of the finished sheets varies widely, depending on the quality of seaweed used. The sheets can be left raw or can be toasted as yakinori or seasoned as ajitsukenori.

The Use of Laver in Wales

Laver has also been wildcrafted for centuries in the British Isles and especially in Wales, along the Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire coasts. Laver or "Lhawvan" was reported to be an important food source and "very much the fuel that fed the people as part of the industrial revolution." (Source)

Freshly harvested laver is traditionally prepared as the Welsh dish known as "laverbread", served as a staple breakfast food.

According to Camden's Britannia (1607),

"Near St Davids, especially at Eglwys Abernon, and in many other places along the Pembrokeshire Coast, the peasantry gather in the Spring time a kind of alga or seaweed, where they made a sort of food called Lhavan or Llawvan, in English, black butter. The seaweed is washed clean from the sand, and sweated between two tile stones. The weed is then shred small and well-kneaded, as they do dough for bread, and made up into great balls or rolls, which some eat raw, and others fry with oatmeal and butter".

Harvesting Nori Seaweed

Even though nori is classified as a red algae, most wild types are actually an olive-green, dark-green and sometimes purple-brown color. The pigment can vary considerably depending on the species of Porphyra growing in different coastal regions.

It's exceptionally important, when harvesting seaweed, to find pristine clean ocean waters away from industrial or developed coastlines.

Nori needs to be gathered at low tide in the summer and fall seasons, when it is most abundant and ready for harvest. When the waterline recedes, during this brief amount of time (usually several hours) blades of laver can be found growing off of rocks, sometimes literally covering them.

The seaweed has a unique shape that grows slightly curved and twisted rather than flat and is not usually more than 31cm or a foot in length. It is important when harvesting nori to be aware of little creatures that like to hide within the curled overlapping fronds. Some believe that this is what may contribute to its mentioned high B-12 content. The seaweed should be thoroughly cleaned right after harvest in seawater to rinse the blades of sand particles and any critters.

If you would like to harvest fresh seaweeds off the Northern Pacific

U.S. coastline and are concerned about radioactive contamination, you can

visit the UC Berkeley sponsored non-profit organization Berkeley RadWatch

website for more information on current findings. According to the Berkeley

RadWatch, "To date, no radioactive cesium that can be

attributed to Fukushima has been observed."

To wildcraft laver it is best to use clippers, cutting off at least 3 inches from the base so it is able to regrow. Once gathered, rinse it in clean seawater and place it in a sack, container or plastic bag.

Seaweeds can be transported in an ice chest or cooler and dried in

another location. If not dried within a few hours they will tend to get slimy

and begin to break down over several days, depending on the outside

temperature. Keeping freshly harvested seaweed in a sealed bag or

container in the fridge will slow down this process.

Because it is not as thick as other seaweeds, like kelp,

it doesn't take long to dry. Unlike wildcrafted herbs, sea vegetables

are generally sun-dried by hanging the gathered pieces on a clothes line

or laying them flat on tarps or dry rocks. This only takes between 3-5 hours to dry in full direct sunlight.

You can store laver

in an airtight glass jar in a cool dark location. This will preserve the

nutrient quality and keep it fresh for the entire year. Most wild harvested dried laver has a sweet taste and develops a pleasant perfume-like fragrance when cured in a sealed jar.

Nori Nutrition

High in Vitamins and Minerals

Seaweeds are nutrient dense foods and, when included in the diet and eaten periodically, can be a valuable source of nutrition, providing potential vitamins and minerals commonly lacking in land-based plant and animal foods. They have, in fact, been used extensively throughout history as livestock feed as well as natural fertilizers for agricultural food crops to increase production and nutritive content.

According to the journal "Preventative Nutrition and Food Science", laver is a bioavailable supplemental alternative containing "an abundance of minerals such as potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, and calcium. From a nutritional perspective, lavers are characterized by high concentrations of fiber and minerals, are low in fat, and have relatively high levels of protein."

P. yezoensis and other species have additionally been shown to be high in iron content. In one study it was observed that iron levels in raw and dried nori were higher than toasted varieties.

Laver contains significant amounts of beta-carotene, vitamin C and a number of B vitamins, like niacin and folic acid. Nutritional value, however, does vary depending on the quality of seaweed and growing, harvesting and processing methods used.

It only takes small amounts of nori used as sheets or as dried seaweed pieces or flakes to provide a daily dose of condensed nourishment. As reported in The Japan Times, the expression “ichinichi nimai isha irazu” translates as “two sheets a day keeps the doctor away.” (*)

A Source of Iodine

Iodine is an especially important mineral needed for healthy thyroid function and hormone production. Because iodine is not naturally produced by the body, it needs to be consumed through ones diet. Seaweeds are whole food sources of dietary iodine that can help protect the thyroid gland and its primary role in regulating metabolism.

Iodine deficiencies are more prevalent today because of daily exposure to bromine, chlorine and fluoride, all of which displace iodine and prevent its proper absorption. Bromine is found in such things as computer plastics, pesticides, soft drinks, baked flour products, medications and fire retardants. Chlorine and fluoride are often found in tap water.

The thyroid can also uptake radioactive iodine, like cesium 137, when there is iodine deficiency. In some cases, as with the nuclear Fukushima disaster, it may also be necessary to take a concentrated iodine supplement.

Laver, relatively speaking, is not as high in iodine content as other sea vegetables, like kelp, sea lettuce, dulse or bladderwrack. According to data collected from Maine Coast Sea Vegetables, 100 grams of kelp is 272,150 micrograms of iodine. Laver contains 7,650 micrograms, WAY LESS iodine than kelp or dulse seaweed which is reported to be 14,200 micrograms.

Some research indicates that health issues may arise when there is either a deficiency as well as an excess of dietary iodine. The lower iodine content, compared to other seaweeds, makes nori safe for long-term use, which is especially relevant for those with iodine sensitivities as it is not as easy to overdose on.

In a clinical study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, it was demonstrated that "dried green and purple lavers (nori) contain substantial amounts of biologically active vitamin B-12 but less of dietary iodine relative to other edible seaweeds." It was additionally noted that "excessive intake of the dried lavers is unlikely to result in harmful intake of dietary iodine."

Contains Omega Fatty Acids and Protein

Nori contains small amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids, a characteristic which tends to be more common in seaweeds from cold water zones. Especially high in omega-3 (ALA) compared to omega-6 (LA), 2T of dried raw laver contains 8.1mg of omega-3 and .4mg of omega-6. According to this nutritional data, laver (particularly those harvested from northern marine waters), provides 16 times more omega-3 than omega-6, making it an excellent choice as an omega-3 food source.

PUFA's or polyunsaturated fats play an important role in regulating inflammation in the body and aid in proper brain and nervous system functioning.

Nori contains good amounts of protein, usually more than dulse. In one 2013 published study, it was stated that, "Lavers are rich in essential amino acids such as methionine, threonine, and tryptophan." Other non-essential amino acids found in large amounts include alanine, aspartic acid, glutamic acid and glycine. These constituents are known to provide for the seaweed's distinctive rich and sweet flavor.

Red algae species of the genus Porphyra are also found to contain antioxidant compounds such as the pigment proteins, chlorophyll and phycoerythrin.

A Source of Beneficial Polysaccharides

Consumed as whole laver or flakes in soups and stews or used as sheet wraps, marine algae's can be a nutritious way to add various polysaccharides to the diet. Polysaccharides help to modulate immune response and red seaweeds, like nori, have been shown to act as prebiotics, helpful for balancing gut microbiota. (*)

In one 2014 study is was shown that the polysaccharides, like porphyran, from the P. yezoensis species had a hypolipidemic effect on rats, decreasing LDL cholesterol and increasing high-density lipoproteins or the "good" cholesterol.

Types of Nori

- Nori Sheets - Available raw, toasted plain or seasoned with sesame oil, salt or other flavorings.

- Dried Laver Pieces - Large pieces of dried seaweed.

- Nori Flakes - Produced from whole seaweed or raw/toasted nori sheets.

Purchasing High Quality Seaweed

When it comes to purchasing your seaweeds, it is always best to choose those coming from a reputable source that offers organic certification and/or tests for possible radioactive isotopes, toxins and heavy metals such as lead, arsenic and cadmium.

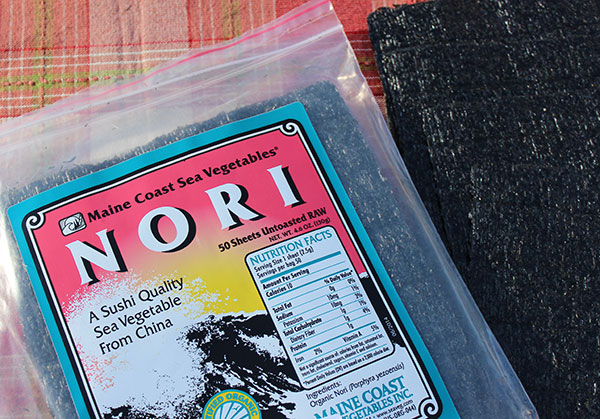

Recommended Nori Brands

Maine Coast Sea Vegetables - Sells both organically certified and tested raw laver pieces as well as raw and toasted sheets cultivated in marine waters off the coast of China from local family-based cooperatives.

Mountain Rose Herbs - As of 2017, offers certified organic seaweeds grown in marine waters off North Atlantic coastlines but can come from the US and Canada based on the season.

Earth Circle Organics - As of 2015, provides raw nori sheets grown in certified organic growing waters in a secluded area located in the Sea of Japan.

Izumi Organic Nori Sheets - A lesser know supplier that offers a certified organic selection grown in controlled seawater locations.

Emerald Cove - Currently, some nori sheet products are certified organic.

How to Use

Whole laver, nori flakes and sheet pieces can be easily added to soups, legumes and grain dishes. The macrobiotic diet and philosophy places a large emphasis on using seaweeds with cooked whole grains as well as beans to improve their digestibility.

Freshly harvested or soaked laver can be added to a raw soup recipe or chopped and prepared in a seaweed salad, miso soup or sautéed with tempeh.

Nori sheets, of course, are appropriate for traditional hand-rolled sushi, but also make a great replacement for tortillas or bread when used as wraps for vegetable fillings, sprouts, seed cheeses, sauerkraut and other whole food ingredients. You can also make your own homemade nori rolls from other grains like wild rice or quinoa.

Sheets of the seaweed can also be used to make a nori nachos recipe, by spreading a layer of raw vegan cheese sauce on top and dehydrating it for several hours. We additionally utilize sheets to make our dehydrated nori sticks (see these two recipes in the links below).

All forms of the seaweed can be ground into a fine flake or powder to use as a low-sodium salt replacement on meals.

Precautions:

While laver has relatively low amounts of iodine compared to other seaweeds, you should avoid consuming large amounts if you have sensitivities to iodine excess. Consult with your health care provider if you have an underactive or overactive thyroid gland, are pregnant or breastfeeding or taking prescription medications.

Shop Related Products (About Affiliates & Amazon Associate Paid Links)

Affiliate Disclaimer: This section contains affiliate product links. If you make a purchase through our recommended links, we receive a small commission at no additional cost to you. Thanks for the support.